From the Great River and Clarence Cannon National Wildlife Refuges:

The toxins in Pokeweed are not completely understood. All parts should be considered poisonous to people and livestock. The berries are eaten by birds, which seem to be immune to the toxins in the fruits, and other animals. Birds disperse the seeds, which can survive in the soil for more than 40 years.

Protecting natural resources, including air, land and water. Also of interest are threatened and endangered species as well as endangered species. Conservation (wildlife, soil, water, etc.) issues also discussed. Topics include: RCRA, CERCLA, Clean Water Act (CWA), NEPA, 404 Permits, EPCRA, FIFRA, and others.

Search This Blog

Friday, July 31, 2015

Union Pacific Reports Environmental Strategies and Goals in Annual CDP Disclosure

From Union Pacific:

Union Pacific Reports Environmental Strategies and Goals in Annual CDP Disclosure

OMAHA, NEB., JULY 31, 2015

Affirming its commitment to protecting the environment now and for future generations, Union Pacific submitted climate change data to CDP and outlined initiatives and investments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. For the second time, the company also reported on its water consumption and responsible management of this resource in CDP's water questionnaire.

The seventh annual public disclosure details Union Pacific's actions to continuously improve environmental performance, including:

- Investing in locomotive technology to support the rail industry's move toward the U.S. EPA's Tier 4 air emissions standards.

- Managing infrastructure, equipment and operations through training and awareness to increase fuel efficiency.

- Creating a multi-disciplinary fuel conservation team, focused, in part, on addressing locomotive fuel, the company's largest greenhouse gas source.

Union Pacific works with Trinity Consultants to compile its greenhouse gas inventory, and Conestoga-Rovers & Associates verified Union Pacific's 2014 greenhouse gas inventory. Conestoga-Rovers & Associates and Trinity Consultants are independent organizations.

Freight trains, on average, are four times more fuel efficient than trucks. That means moving freight by rail instead of trucks reduces greenhouse gas emissions by an average of 75 percent.Union Pacific can move one ton of freight 475 miles on a single gallon of diesel fuel and is working to develop new technology to improve fuel efficiency.

About Union Pacific

Union Pacific Railroad is the principal operating company of Union Pacific Corporation (NYSE: UNP). One of America's most recognized companies, Union Pacific Railroad connects 23 states in the western two-thirds of the country by rail, providing a critical link in the global supply chain. From 2005-2014, Union Pacific invested more than $31 billion in its network and operations to support America's transportation infrastructure. The railroad's diversified business mix includes Agricultural Products, Automotive, Chemicals, Coal, Industrial Products and Intermodal. Union Pacific serves many of the fastest-growing U.S. population centers, operates from all major West Coast and Gulf Coast ports to eastern gateways, connects with Canada's rail systems and is the only railroad serving all six major Mexico gateways. Union Pacific provides value to its roughly 10,000 customers by delivering products in a safe, reliable, fuel-efficient and environmentally responsible manner.

The statements and information contained in the news releases provided by Union Pacific speak only as of the date issued. Such information by its nature may become outdated, and investors should not assume that the statements and information contained in Union Pacific's news releases remain current after the date issued. Union Pacific makes no commitment, and disclaims any duty, to update any of this information.

Fence Marking Project Protects Sage Grouse

From the #USDA:

Posted by Ron Francis and Lori Valadez, Natural Resources Conservation Service, Utah, on July 30, 2015 at 11:00 AM

Clip-on plastic reflective fence markers allow the sage grouse to see fences on the landscape. Photo by Jeremy R. Roberts, Conservation Media

In the “Old West”, barbed wire fences were often cut to allow trailing droves of cattle through. In the “New West,” livestock fencing is being marked to help reduce collisions for sage grouse and other wildlife.

Sage grouse are especially at risk of hitting fences that are close to established leks, spring courtship dancing grounds, where males usually fly in the dark to gather. The flatter the landscape, the harder it is for the grouse to see the fences. In the most at-risk landscapes, biologists estimate an average of one collision for every mile of fence.

Through the Sage Grouse Initiative (SGI), USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) is working with ranchers to improve habitat for sage grouse, an at-risk bird considered for listing under the federal Endangered Species Act. To date, NRCS has funded $296.5 million nationwide to restore and conserve sage grouse habitat.

In Utah, sage grouse efforts are being amplified even further through partnerships. NRCS encourages a variety of conservation practices to improve habitat for sage grouse, including marking fences.

Fence marking can improve the habitat for sage grouse by reducing collisions. Photo by Jeremy R. Roberts, Conservation Media

NRCS purchased enough clip-on plastic reflective fence markers for 138.5 miles of fence lines in Utah and provided them free to people and organizations willing to volunteer their time to install them on private lands.

Once the project was announced, conservation partners, such as the Mule Deer Foundation, Utah Dedicated Hunters, conservation districts and the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, helped round up volunteers that included local boy scouts, hunters, university students and private landowners.

NRCS Utah State Conservationist Dave Brown was sure Utahns — known for their volunteerism — would be willing to complete the task, and he was right. Last year, more than 70 volunteers spent 279 hours installing 250,000 fence markers on nearly 138.5 miles of fence lines.

Recent research shows these fence markers can help reduce sage grouse fence collisions by 83 percent. With the permission of private landowners, volunteers placed a mixture of red and white markers on the top wire of fences. White markers are seen well by grouse in summer, while red contrasts with winter snow.

Published estimates report a six-fold decline in collisions along marked versus unmarked fences. Using these rates, the SGI’s fence-marking efforts across the 11-state range, including Utah, are preventing 2,600 fence collisions annually, which is more than twice the number of males counted annually on leks in Washington, North Dakota, South Dakota and Canada combined.

To help determine the correct three-inch placement of markers, a fence collision risk tool was developed and is used by wildlife agencies and federal biologists to define areas near leks where placement of the fence markers would be most effective.

Learn more about NRCS’ wildlife conservation efforts. To get started with NRCS, visit your local USDA Service Center or www.nrcs.usda.gov/GetStarted.

Sage grouse are especially at risk of hitting fences that are close to established leks.

Related Posts

Wednesday, July 29, 2015

Near-record python bagged at Everglades National Park | Miami Herald

A massive python slithering along the tram road at Shark Valley in Everglades National Park may be one for the record books.

Nabbed by University of Florida researchers studying invasive species in the park earlier this month, the female measured 18 feet, three inches and weighed 133 pounds. That’s three inches shy of the record-holder — beheaded by a man riding an ATV in Florida City in 2013 — but five pounds heavier than previous snakes captured in the Florida wild.

Near-record python bagged at Everglades National Park | Miami Herald

Tuesday, July 28, 2015

Wildfire-Related Tragedy Leads to Landmark Forest Restoration Partnership

From the #USDA:

Posted by L.F. Chambers, Office of Legislative Affairs, U.S. Forest Service, on July 28, 2015 at 11:00 AM

In July/August 2013 the Forest Service and City of Flagstaff, Arizona conducted a pilot project off FR240 (Schultz Pass Road) to assess impacts and capabilities of two types of logging equipment on steep slopes and best methods for slash piling on slopes (to allow for the greatest consumption during prescribed pile burning). (FWPP photo)

The Schultz Fire of 2010 started with an abandoned campfire. High winds blew the flames into neighboring trees and brush, igniting a wildfire that would grow to 15,000 acres of the Coconino National Forest and threaten residents near Flagstaff, Arizona. In the following days 750 homes would be evacuated. It took 300 firefighters several weeks to contain the fire in the steep slopes North and East of the city.

Flagstaff had been spared from fire, but not its aftermath. In July 2010, heavy flooding due to monsoonal rain events on the burned-over slopes of the San Francisco Peaks caused an estimated $133-147 million in damage to neighborhoods just outside the city. A 12-year-old girl, Shaelyn Wilson, was killed when she was swept away in a flash flood.

“The danger doesn’t stop when the last embers go out,” said Erin Phelps, a Forest Service employee and leader of a multi-agency team on the Flagstaff Watershed Protection Project, an innovative partnership founded in the wake of the tragic floods. “If such disastrous floods could happen in these neighborhoods, they could also happen to the city of Flagstaff.”

In addition to the clear dangers to life and property presented by wildfire and subsequent floods, reports indicated that a similar fire could threaten as much as 50 percent of the city’s drinking water supply. Recognizing these dangers, residents of Flagstaff passed a $10 million bond to fund treatments on federal, state, and city land to improve their resilience to wildfire. As a result of this foresight and community support, the Flagstaff Watershed Protection Project was founded in November 2012.

The Forest Service has since worked closely with representatives from the city, state and county as well as local Native American tribes and non-governmental agencies to plan the restoration projects that will remove the dense stands of timber around Flagstaff. Public involvement and input have been crucial to their progress.

Phelps and her team have received more than 500 individual comments from the public during the most recent comment period alone. They’ve also taken citizens and local leaders to particular areas and shown them what needs to be done in order to reduce the wildfire risk in the steep, technical slopes within the project site. The project will use a mix of helicopter and cable-logging alongside traditional ground-based harvesting equipment to remove selected trees from unhealthy stands, developing forests that are more resilient to wildfire.

“There is a real sense of urgency about this work,” Phelps said. “The partners on this team all feel an added accountability to each other and the public, and everyone understands the urgency in restoring the forest around Flagstaff.”

The Forest Service released its draft decision in June 2015 on how to proceed with this fire hazard reduction work, and following the objection and objection resolution periods, implementation could begin as soon as late 2015. Phelps says the decision will directly reflect public input and include a blending of treatments based on the comments received.

The project has been driven by public input and involvement at every step. One example Phelps cites is the issue of “viewsheds.” The Flagstaff Watershed Protection Project received many comments about potential damage to the beautiful views that residents place such a high value on. Those comments helped determine where to use helicopter logging in the steep peaks, a form of logging that has less impact to forest resources than other types of operations but is also more expensive.

“The official environmental planning process has been a great opportunity to work with the public to weigh the different tradeoffs of various treatment methods on ecosystem services, such as cable logging versus helicopter logging and the impacts of those on recreation, economics and viewsheds,” Phelps said. “It’s critical that we understand what they want from this process, so we can provide them a healthy landscape but also protect their other interests as well.”

Phelps, a trail runner and mountain biker, also has a personal stake in all of this.

“I love to spend time in the mountains above Flagstaff,” she said. “This project will help protect our city, our neighborhoods and our water, but it will also help protect the areas Flagstaff residents use for recreation and ultimately, the reason they call this area home.”

This post is part of a series featuring the Forest Service’s work on restoration across the country.

Related Posts

Tags: Arizona, California, Coconino National Forest, disaster, flood, Forestry, FS, resilience, restoration, water, Wildfire, wildfires

Anise Hyssop

From the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Midwest Region:

Attract butterflies and hummingbirds to your pollinator garden with anise hyssop!

Photo: Anise hyssop bud by Katie Steiger-Meister/USFWS.

Attract butterflies and hummingbirds to your pollinator garden with anise hyssop!

Photo: Anise hyssop bud by Katie Steiger-Meister/USFWS.

Portman Hosts Lake Erie Water Quality Townhall

Published on Jul 28, 2015

On Friday, July 24, 2015, U.S. Senator Rob Portman (R-Ohio) hosted a townhall for state, local, and federal experts to discuss the condition of Lake Erie and current threats such as Harmful Algal Blooms, invasive species like Asian Carp, and pollution.

Monday, July 27, 2015

Black-necked Stilt

From the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service:

Today is "Walk on Stilts Day"! Black-necked Stilts like this one walk delicately, and tilt forward to pick food with a needle-like bill. Stilts have the second-longest legs in proportion to their body in the bird world, exceeded only by the flamingo.

Rinus Baak / USFWS

Today is "Walk on Stilts Day"! Black-necked Stilts like this one walk delicately, and tilt forward to pick food with a needle-like bill. Stilts have the second-longest legs in proportion to their body in the bird world, exceeded only by the flamingo.

Rinus Baak / USFWS

Lythrum alatum (Winged Loosestrife)

From Great River and Clarence Cannon National Wildlife Refuges:

Lythrum alatum (Winged Loosestrife) is a native plant and should not be confused with Lythrum salicaria (Purple Loosestrife). The latter is an aggressive Eurasian plant that invades wetlands and forms dense stands that exclude other species. Many kinds of insects visit the flowers, including various long-tongued bees, green metallic bees, bee flies, butterflies, and skippers.

Lythrum alatum (Winged Loosestrife) is a native plant and should not be confused with Lythrum salicaria (Purple Loosestrife). The latter is an aggressive Eurasian plant that invades wetlands and forms dense stands that exclude other species. Many kinds of insects visit the flowers, including various long-tongued bees, green metallic bees, bee flies, butterflies, and skippers.

Sunday, July 26, 2015

Rufous Hummingbird

From the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Mountain-Prairie Region:

A rufous hummingbird feeds on flowers of Rocky Mountain Beeplant on Seedskadee NWR. Photo Credit: Tom Koerner/#USFWS

A rufous hummingbird feeds on flowers of Rocky Mountain Beeplant on Seedskadee NWR. Photo Credit: Tom Koerner/#USFWS

Green Heron

From U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Midwest Region:

Green herons are one of the very few tool-using birds. They’ll often use twigs, insects and other objects to lure fish in!

Photo: Green heron courtesy of Steve McManes.

Green herons are one of the very few tool-using birds. They’ll often use twigs, insects and other objects to lure fish in!

Photo: Green heron courtesy of Steve McManes.

Thursday, July 23, 2015

Recognizing the Value of Cleaner Watersheds

From the #USDA:

Posted by Jonas Epstein, National Forest System, U.S. Forest Service, on July 23, 2015 at 11:00 AM

A watershed in the Stanislaus National Forest, located in the Sierra Nevada region of California. Photo credit: US Forest Service

The mission of the Forest Service is to “sustain the health, diversity and productivity of the Nation’s forests and grasslands to meet the needs of present and future generations.” The provisioning of water resources – notably clean drinking water and flood control – is central to this. Growing demand for our water resources, spurred by population growth, and the effects of climate change further challenge the Forest Service to successfully meet the needs of present and future generations.

In the western United States – where water flowing from national forests makes up nearly two-thirds of public and commercial water supplies – water scarcity and wildfire threats have galvanized diverse stakeholders to invest in healthy headwaters. Local communities, public utility companies, businesses, non-governmental organizations and state and local agencies are investing in watershed restoration to avoid catastrophic economic losses.

Catalyzed by the devastation resulting from the 2013 Sierra Nevada Rim Fire, the Nature Conservancy and Forest Service co-sponsored an economic analysis of proactive fuel treatment and restoration in the Mokelumne watershed. The study found the benefits of management actions (valued between $126 and $224 million) to exceed cost of treatment ($68 million) by a ratio of two to one, calculated conservatively over a 30-year time period. These benefits stem from saved structures and timber, avoided fire cleanup, road repairs, sediment treatment for utilities and carbon sequestered. These returns on investment do not even include the ancillary impacts of habitat loss or recreation expenditures foregone.

Bolstered by the results of this analysis and the devastating impacts of past wildfires, public and private-sector parties in Denver; Flagstaff, Arizona; Santa Fe, New Mexico; Eugene, Oregon; the Sierra Nevada Range in California and others have adopted investment strategies designed to support restoration of headwaters to increase resiliency and protect source water. While the financial mechanisms and oversight varies in each project, implicit in these partnerships is public consensus around the need for collective action and financial support in order to manage ecosystem threats before wildfires become a reality. In many instances, the public has even assumed the cost of paying for proactive source water protection – either through higher water usage rates, or through voting for municipal bonds towards headwaters-based restoration activities.

Like a number of forests in the West, national forests in the eastern United States are beginning to realize the potential to stimulate landscape-scale restoration by linking with downstream communities and businesses to protect water quality. However, the context in the East is dramatically different from the West; with more concentrated population centers, different ecological regimes, and a varied patchwork of landownership, the restoration goals and value-added of forested headwaters differ greatly in the eastern United States.

In order to realize the full potential of watershed investment partnerships, the Forest Service is developing national-level guidance for strengthening current partnerships while providing the tools to connect with a more diverse array of stakeholders to help achieve regional objectives. This initiative emphasizes flexibility, allowing for sharing and collaboration with Federal agency counterparts while still leveraging local and regional finance options and building on existing relationships and networks. As the Forest Service seeks to better understand the connections between ecosystem function and social well-being, the agency is focusing on an ecosystem services approach to “all-lands” management and restoration.

The Forest Service is working to expand the use of investments in a way that allows stakeholders to identify shared interests around their water needs. This is part of a broad suite of work that the Forest Service is doing with partners around restoration for water resources across the country. This month, we will be continuing to highlight such projects to celebrate the important role that national forests play in providing clean water for the public.

The Sierra Nevada Range provides more than 60% of California’s developed water supply. The Sierra Nevada Watershed Improvement Program and its restoration partnership is focused on maintaining ecosystem services critical to the region, including water quantity and quality improvement, reduced greenhouse gas emissions, improved socioeconomic and public health, improved fish & wildlife habitat, enhanced air quality and ultimately, reduced risk of damaging wildfire. After an initial $7.5 billion water bond was passed last year, the Sierra Nevada Conservancy has been tasked with developing criteria to allocate funding. Additionally, USDA is providing $130 million in federal agency watershed restoration projects in the region in response to drought.

This post is part of a series featuring the Forest Service’s work on restoration across the country.

Related Posts

Chef Creates a Sustainable Menu Using Food Waste

Where most people would see cauliflower leaves and the tops of carrots as garbage, Bruce Kalman sees ingredients to actual meals.

The chef of Union in Pasadena uses these ingredients, along with other produce items that many would simply throw away, in juices, sauces and garnishes.

Chef Creates a Sustainable Menu Using Food Waste

Technology Enables Vermont Dairy Farmer to Measure Positive Impacts of Conservation

From the #USDA:

Posted by Amy Overstreet, Natural Resources Conservation Service, Vermont, on July 23, 2015 at 10:00 AM

NRCS Soil Conservationist Danny Peet, left, worked with Vermont farmer Lorenzo Whitcomb to implement edge-of-field water quality monitoring in an effort to minimize impacts to water quality from agricultural runoff.

Stewardship and cutting-edge technology are nothing new to the North Williston Cattle Company, a Vermont dairy farm that uses solar energy and robotic milking machines. The latest advancement on the 800-acre, 224-head operation are edge-of-field water quality monitoring stations, which measure water quality and the benefits of using conservation practices on the dairy farm.

Lorenzo Whitcomb, one of the managers of the family-run dairy, worked with USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) to install the monitoring stations. NRCS has made technical and financial assistance available to farmers in key watersheds across the country.

“The results from this study will illustrate to farmers more precisely the real benefits that conservation practices have on water quality,” said Kip Potter, NRCS water quality specialist.

The Winooski River is the largest watershed that flows into Lake Champlain – nearly 10 percent of the state’s land area. By measuring and recording what is in the water that drains off his fields, Whitcomb can adapt his farming practices.

This technology is helping farmers better understand their soils and how they behave. Different soils have different degrees of permeability, a characteristic that determines how water flows through the soil, and specifically, the rate at which a measured quantity of water drains away through the soil.

Conservation practices can help protect and improve soil health, and in turn, minimize impacts to water quality. Some of these practices include rotating crops, planting cover crops, installing filter strips and field borders, and injecting manure as a fertilizer into the ground.

In addition to NRCS, other partners include the University of Vermont Extension, USDA’s Agriculture and Food Research Initiative, Vermont Agency of Agriculture, Vermont Agency of Natural Resources and Lake Champlain Basin Program.

The data is part of a six-farm monitoring and evaluation program underway in Vermont. Whitcomb’s monitoring stations will help researchers understand leaching in the soil as well as financial and social barriers to implementing conservation practices, like monitoring stations.

“These stations are an incredible asset, and we wanted to see them used to their full extent, collecting data on real Vermont farms, and continuing to inform both the scientific and agricultural communities,” said Joshua Faulkner, farming and climate change program coordinator at UVM Extension.

The two edge-of-field monitoring stations were placed in cornfields bordered by the Winooski River. One of the stations measures water quality on a field where conservation practices are in place, and the other where none are in place, said NRCS Soil Conservationist Danny Peet, who worked with Whitcomb.

Nutrients, like phosphorus and nitrogen, and sediment can wash off farms and other lands. Conservation practices help prevent that. While phosphorus and other nutrients are essential for plant growth, too much can lead to negative impacts, including algae blooms. Lake Champlain suffers from high levels of nutrients, which lead to periodic algae blooms.

“This study is groundbreaking because it’s helping farmers and conservationists think about conservation planning in a new way,” NRCS State Conservationist Vicky Drew said.

Whitcomb learned about the technology during a meeting of the Lake Champlain Valley Farmer’s Coalition, a cooperative of Vermont farmers in the Lake Champlain Basin who are concerned about their impact on the lake.

“This helps me understand what’s going on out in the field, even when I can’t be out there,” Whitcomb said. “Farms can be looked at as filters.” And this edge-of-field monitoring technology provides Whitcomb with a closer look at how his farm impacts natural resources and what he can do to continue protecting and improving natural resources.

To get started with NRCS, visit your local USDA Service Center or www.nrcs.usda.gov/GetStarted.

Lorenzo Whitcomb explains the soil and water quality benefits of conservation practices such as manure injection, cover crops and reduced tillage.

Related Posts

Wednesday, July 22, 2015

Florida’s war on invasive species drags on | Miami Herald

In the war with invasive species, Florida is winning some skirmishes but far from vanquishing its formidable enemies.

On Wednesday, researchers and government agencies gathered in Davie for an annual summit to talk about the latest findings on exotic threats to Florida, from slimy New Guinea flatworms that threaten native snails to the poster snake for invasive species, the Burmese python.

Read more here: http://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/environment/article28372429.html#storylink=cpy

Florida’s war on invasive species drags on | Miami Herald

Wading Buck

From the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Midwest Region:

The fluctuating Mississippi River makes Middle Mississippi River National Wildlife Refuge a mosaic of temporary wetlands, mud flats and sand deposits.

Photo: Wading buck by Cathy Henry/USFWS.

The fluctuating Mississippi River makes Middle Mississippi River National Wildlife Refuge a mosaic of temporary wetlands, mud flats and sand deposits.

Photo: Wading buck by Cathy Henry/USFWS.

Illinois Releases Final State Nutrient Loss Reduction Strategy to Reduce Pollution Loading to Illinois Waters and the Gulf of Mexico

Strategy Emphasizes Coordinated, Voluntary and Cost-Effective Efforts

Illinois.gov - Illinois Government News Network (IGNN) - Search the News Results

Illinois.gov - Illinois Government News Network (IGNN) - Search the News Results

Could Forest Thinning Help Ease Water Shortages in the United States?

From the #USDA:

Posted by Stephanie Worley Firley, U.S. Forest Service Eastern Forest Environmental Threat Assessment Center, on July 22, 2015 at 10:00 AM

Researchers found that thinning could boost water yield, but the results are not proportional. Photo by U.S. Forest Service.

Planning for the future of the nation’s water resources is more important now than ever before as severe drought grips the West, affecting heavily populated areas and critical agricultural regions. Forests generally yield huge quantities of water—much more than crops or grasslands—but also use a lot of water during the growing season, so some land managers wonder if forest thinning could boost water supplies to people and ecosystems in a changing climate.

U.S. Forest Service researchers from the Eastern Forest Environmental Threat Assessment Center and the Coweeta Hydrologic Laboratory tested this idea and found that the results were not so cut and dried. Their findings were recently published in a special issue* of the journal Hydrological Processes.

The researchers examined how water yield could change with various levels of forest thinning based on reductions in Leaf Area Index (LAI)—the ratio of leaves per unit of ground area, which provides a measure of forest productivity and water use. The researchers considered the effects of LAI reduction in the context of climate and used the Water Supply Stress Index (WaSSI) model to simulate water yields based on combined changes in LAI, temperature and precipitation as well as four future climate scenarios across 2,100 U.S. watersheds.

Model results indicate that thinning could increase water yield, but LAI reduction and water gains are not proportional. Even with substantial thinning, water yield increases were relatively minimal. “As a whole across the United States, water yield could increase by 3 percent, 8 percent and 13 percent if LAI is reduced by 20 percent, 50 percent and 80 percent, respectively,” says Ge Sun, Eastern Threat Center research hydrologist and the study’s lead author.

Changes in temperature and precipitation also have profound effects on water yield due to their influence on evapotranspiration—the combination of evaporation and water uptake through roots. “Temperature increases of 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) could increase forest water use and decrease water yield by 11 percent. If precipitation is reduced by 10 or 20 percent, forest water yields could decrease by 20 or 39 percent, respectively,” says Sun.

In already wet or moderately wet areas of the country, forest thinning could lead to greater increases in water yield compared to drier areas. But since these increases in water yield are directly related to precipitation trends, excessive forest thinning could lead to flooding.

In dry areas where water is needed most, managers may thin forests to reduce wildfire risk, which could make soil water more available to remaining trees and improve overall forest heath. Any increases in water yield could be an added bonus in some cases. Still, researchers are challenged to project water yield as future climate change could lead to significant shifts in forest dynamics. The historically water-rich South, for example, is becoming drier—a trend that is expected to continue over the next several decades.

Uncertainty is an inherent part of planning, especially in the face of climate change, but managers should remain vigilant to sustain forests and their critical services.

“Mitigating and adapting to climate change impacts on forest water supplies will require innovative management approaches, which could include thinning. But forest managers must preserve forest values and balance the tradeoffs among water quantity, quality, carbon sequestration, management costs and other benefits and concerns,” says Sun. “Now and in the future, active conservation and management efforts are critical to protect our forests, which are the main sources of clean water for many metropolitan areas and aquatic ecosystems.”

*This special issue of Hydrological Processes includes research presented at the 3rd International Conference on Forests and Water in a Changing Environment held in Fukuoka, Japan in 2012.

Related Posts

Bog Turtle

From USFWS Endangered Species:

To all of our Maryland followers out there: there are 25 endangered species in the Old Line State, including America’s tiniest turtle, the bog #turtle.http://1.usa.gov/1LQiTy2 Which one is your favorite? (Photo: bog turtle hatching. Credit: Rosie Walunas, USFWS)

To all of our Maryland followers out there: there are 25 endangered species in the Old Line State, including America’s tiniest turtle, the bog #turtle.http://1.usa.gov/1LQiTy2 Which one is your favorite? (Photo: bog turtle hatching. Credit: Rosie Walunas, USFWS)

Bald Eagle

From the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Midwest Region:

A bald eagle released nearly 3 decades ago in Indiana is still flying and raising chicks. She is among the oldest banded eagles ever recorded! See her story:http://go.usa.gov/3GefW

Photo: Bald eagle courtesy of Teresa Bass.

A bald eagle released nearly 3 decades ago in Indiana is still flying and raising chicks. She is among the oldest banded eagles ever recorded! See her story:http://go.usa.gov/3GefW

Photo: Bald eagle courtesy of Teresa Bass.

The salmon are coming back!

From Sitka National Historical Park:

The salmon are coming back! Dozens of pink salmon can be seen jumping in the ocean next to the visitor center and gathering in the Indian River estuary. Want to learn more about salmon and their ecological and cultural importance? Then come attend a ranger-led Salmon Discovery Talk! The schedule for upcoming talks can be found at http://www.nps.gov/sitk/

The salmon are coming back! Dozens of pink salmon can be seen jumping in the ocean next to the visitor center and gathering in the Indian River estuary. Want to learn more about salmon and their ecological and cultural importance? Then come attend a ranger-led Salmon Discovery Talk! The schedule for upcoming talks can be found at http://www.nps.gov/sitk/

Tuesday, July 21, 2015

Blue Dasher

From Muscatatuk National Wildlife Refuge:

Did you know there are at least 38 different kinds of dragonflies on Muscatatuck? Ralph Cooley captured this blue dasher with his camera at Lake Linda. Thanks for sharing Ralph! Photo: Ralph Cooley

Did you know there are at least 38 different kinds of dragonflies on Muscatatuck? Ralph Cooley captured this blue dasher with his camera at Lake Linda. Thanks for sharing Ralph! Photo: Ralph Cooley

Crawfish Frog

From USFWS Endangered Species:

We love how intricately intertwined and efficient nature is! The crawfish frog in southeastern Indiana uses old crayfish burrows to live in. Scientists believe that crawfish frogs evolved with the buffalo trace where millions of bison migrated from the Midwest prairies to Tennessee. Crawfish frogs appear to be in decline now but biologists are working to understand their habitat requirements and biological needs so they can figure how to protect and restore their habitat. Learn more about crawfish frogs and other amphibians:http://1.usa.gov/1HOIIwM (Photo: Crawfish frog in burrow, Andrew Hoffman)

We love how intricately intertwined and efficient nature is! The crawfish frog in southeastern Indiana uses old crayfish burrows to live in. Scientists believe that crawfish frogs evolved with the buffalo trace where millions of bison migrated from the Midwest prairies to Tennessee. Crawfish frogs appear to be in decline now but biologists are working to understand their habitat requirements and biological needs so they can figure how to protect and restore their habitat. Learn more about crawfish frogs and other amphibians:http://1.usa.gov/1HOIIwM (Photo: Crawfish frog in burrow, Andrew Hoffman)

The Climate Hubs Tool Shed - An Inventory of Relevant Tools to Help Land Managers Respond to Climate Variability

From the #USDA:

Posted by Rachel Steele, National Climate Hubs coordinator, on July 21, 2015 at 1:00 PM

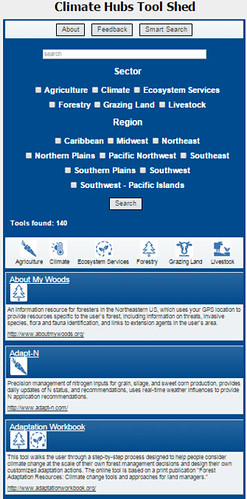

Users can search using keywords, user-friendly categories, or a combination of variables via the advanced search feature. (Click to enlarge)

Producers want tools that can help implement adaptation strategies to reduce climate-related pressures and ensure the quality of production. They also need information about the effects of climate change on production systems. These range from management of labor resources in specialty crop production, to market demand for nursery crops, to marketing of locally grown produce. The Climate Hubs Tool Shed can be used to develop innovative management systems that increase profitability and product quality across all systems.

Launched in early 2014, USDA’s Regional Climate Hubs were established to deliver science-based knowledge, practical information, and program support to farmers, ranchers, forest landowners, and resource managers. To this end, the Hubs are excited to announce the release of the Climate Hubs Tool Shed. The Tool Shed is an online, searchable database of tools (data-driven, interactive websites and mobile apps) that can assist land managers, land owners, and extension professionals in adapting working lands to the impacts of climate change. Users can search using keywords, user-friendly categories, or a combination of variables via the advanced search feature. While many of these tools were developed specifically to adapt to climate variability, several were developed to aid in mitigating the indirect effects of climate change such as drought, pests, wildfire, and extreme weather.

The Climate Hubs Tool Shed is an excellent resource for managing the effects of climate change on working lands. Consolidating the tools in one place helps users find the best tool for their specific need. So take a look at the Tool Shed on the Climate Hubs Website. Feedback is always welcome, and can be provided via the “Feedback” button on the site. The Climate Hubs Tool Shed was developed by the Southeast Climate Hub, but is relevant and can be used by land managers across the country. Special thanks to Sarah Wiener, Emrys Treasure, and Steve McNulty of the Southeast Climate Hub for seeing this project to completion.

Producers need information about the effects of climate change on production systems, like irrigation for example.

Related Posts

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)